Voters in remote Aboriginal communities lodge discrimination complaint against Australian Electoral Commission

Date: Oct 5, 2021

Publication Type: Blog

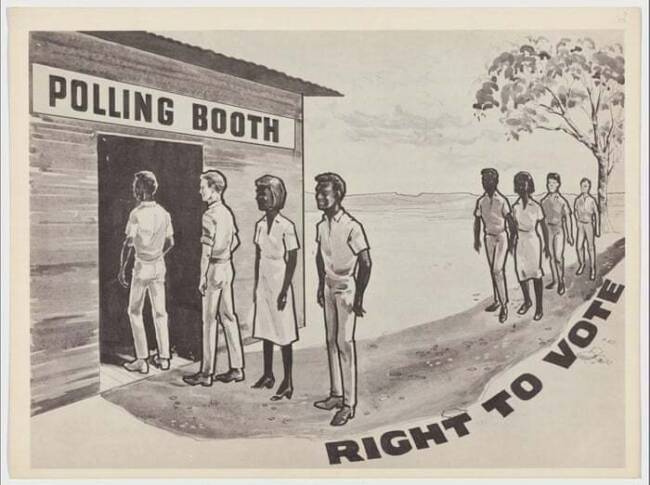

Compulsory voting in Australia has always had a racial taint. Most people would associate the term “voter suppression” with the many and varied electoral systems and “Jim Crow” laws in the United States or the operation of electoral systems by autocratic regimes, but not with the operation of Australian electoral regimes.

That all changed in June with the filing of a complaint that the national agency charged with the conduct of Federal elections and the maintenance of the Australian electoral roll was itself guilty of voter suppression based on race.

Non-Aboriginal Australians have had universal suffrage since 1902 and been required to enrol since 1911, and vote since 1924, but it took half a century - until 1962 - before the Commonwealth Electoral Act was amended to give Aboriginal people the right to vote in Federal elections.

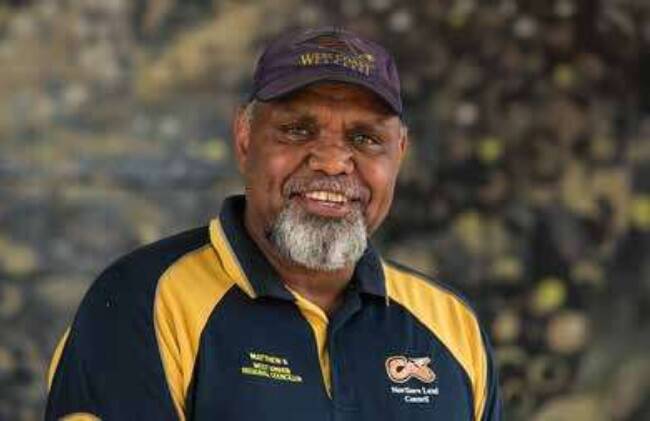

Matthew Ryan, Mayor of the West Arnhem Council.

For Aboriginal people enrolment was voluntary but once enrolled, voting was compulsory. Compulsory enrolment for Aboriginal people wasn’t legislated until 1984.

On 15 June two Aboriginal men - Matthew Ryan and Ross Mandi - filed a complaint to the Australian Human Rights Commission (the AHRC) against the Australian Electoral Commission (the AEC) alleging that the AEC has effectively suppressed the Aboriginal vote in remote areas in the Northern Territory.

They claim the AEC has done this by failing to implement its own mandate that allows it to directly enrol eligible persons who are not on the electoral roll or to update personal details, by using electronic data readily and lawfully accessed from trusted government agencies, including motor vehicle registries, Centrelink and the Australian Taxation Office.

Mr Ryan lives at Maningrida and Mr Mandi lives at Galiwin’ku. Maningrida and Galiwin’ku are respectively the sixth and eighth largest towns in the NT with populations at the 2016 Census of 2,300 and 2,100.

Both are in the Federal seat of Lingiari which has an Indigenous population of 41.7 per cent, the highest of any electorate in the country.

As with many remote communities in the NT, Maningrida and Galiwin’ku have seen their populations grow by around 40 per cent since 2001.

The AEC policy at the core of the complaint concerns the performance of its functions under the Electoral Act in relation to the maintenance of the Commonwealth electoral roll - which is also used in NT Parliamentary elections.

In 2012 the policy, known as Federal Direct Enrolment and Update (FDEU), was developed following an amendment to the Electoral Act designed to arrest an ‘alarming’ downward-trending nation-wide drop in enrolments in 2009 to just over 91 per cent.

The FDEU has been lauded by the Australian Electoral Commissioner, Tom Rogers, who claims it produced ‘the best roll since Federation’ and was a ‘modern miracle’ for the 2019 Federal election with a 97 per cent enrolment.

The FDEU was not so miraculous however for those remote residents of Lingiari (which covers most of the NT apart from Darwin and the satellite city of Palmerston that together form the electorate of Solomon) and Durack in Western Australia which are both in the lowest electoral enrolment band of 75 to 80 per cent.

Most of the remote residents of Lingiari do not receive mail directly to their homes, i.e. by Australia Post, but do so through a community post office, by mail bag or post box.

Notwithstanding the absence of numbered letter boxes affixed to a neat white picket fence outside every house, one by-product of the Federal Intervention in the NT from 2007 to 2012 is that most larger communities in the NT now have accurately-surveyed house lots that are now incorporated into the NT’s land registration system.

Similarly, most remote housing is subject to tenancy agreements that identify the tenants for each house, which in turn are - perhaps less consistently - usually readily identifiable either by a locally-relevant house number visible from the street or by colours, i.e. “the blue house on Rainbow Street.” Street names and signs have been implemented in most remote communities as part of the “normalisation” regime of the NT Intervention.

Another complaint by Mr Ryan and Mr Mandi concerns the differential treatment for remote Aboriginal community residents in Lingiari where they were allocated a polling booth on or prior to polling day (usually serviced by remote mobile polling teams) that operated for a substantially shorter time than booths at similarly sized towns in the NT such as Nhulunbuy, Tennant Creek and Jabiru.

The Maritime Union of Australia and the United Workers Union supported the Arnhem Land men in lodging their complaint.

“The AEC must urgently change this discriminatory policy so that Indigenous people are better able to reach a ballot box during elections, and so they are no longer turned away at the ballot box en masse,” MUA national Indigenous Officer Thomas Mayor said.

A date for the conciliation of the complaint to the AHRC has yet to be set.

*First published at the Crikey.com.au blog, The Northern Myth on 21 June 2021